Houston media all boo-hoo over school budget cuts. They didn't notice the cliff?

Revenue down hundreds of millions, Houston school district partied like Kardashians.

This is a story about the way we in the journalism trade tend to report stories about money, and let me say at the top I’m not blaming us. Money is an especially tough topic for us, because we don’t have any. We’re just not that into it.

Houston Landing, an online publication staffed by some of Houston’s most experienced and capable ink-stained wretches, published a story last week that was a regrettable instance of what I speak. It said the school system was about to wrench comfort and sustenance from impoverished children in order to serve the selfish aims of the superintendent of schools.

What the story failed to note – big omission – was that the school district is headed for a disastrous budget crash left behind by the previous administration. The subsequent mayhem that will ensue if this disaster is not headed off would dwarf the ongoing state takeover of the district.

The ongoing takeover is about the district’s egregious academic failure, which, yeah, sure, the legislature kind of cares about. If the district doesn’t straighten up its cash drawer in a hurry, that will be about money. The legislature will kill for money.

The top of the Houston Landing story said: “Houston ISD will eliminate many of the specialists who work on school campuses to serve students struggling with poverty-related issues, such as hunger and homelessness.”

The story told readers the reason for slashing services for poor children was to fund the academic reform programs of Mike Miles, the superintendent of schools. Miles was imposed on Houston by the state last year after the state disbanded the elected school board and fired the previous superintendent of schools.

“HISD is expected to cut hundreds of millions of dollars from its budget next year,” The Landing said, “to offset the costs of Miles’ sweeping changes to the district under his ‘New Education System’ model.”

So, more or less for fun.

It’s true that Miles’ pedagogical reforms are not without significant cost. I can’t get a number yet, because Miles hasn’t provided the number to his board. That happens this coming Thursday. I would guess it’s going to be somewhere between seventy and a hundred million.

Worth mentioning is that his reforms will produce a system that spends about 50 percent more on poor kids than other kids. Also worth mentioning is that whatever he budgets for his reform program will go to his reform program.

There will be a ledger. We will be able to trace the money. We will be able to see what he said the money would do, and we can find out if it worked.

That is opposed to the way the prior regime spent money -- more or less the Christmas list method, which we will get to in a moment. But long before we go to that point, we need to visit the stark reality left behind by that previous regime – the elected folks who wanted to keep everybody happy. And this is simple. It’s arithmetic.

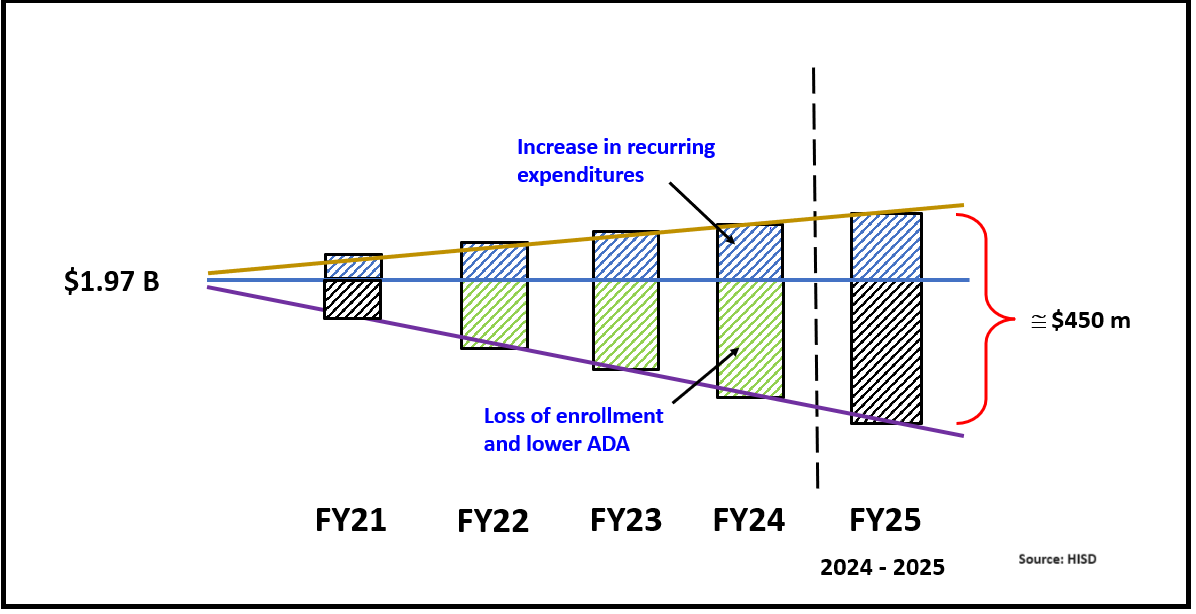

All told, when all the allowances, subsidies and stipends are added up, the school district gets $10,000 per kid from the state. That number hasn’t changed since 2019.

Since 2019, student enrollment in HISD has decreased by 20,000 students to a current level below 190,000. That’s a revenue loss of $200 million. So you and I might assume the district was cutting expenditures all that time to avoid going into the ditch.

Wrong. While its student population was dropping, the Houston school district was spending like an over-served sailor. Departmental budgets soared. The school board even approved a 9 percent pay increase for its 10,000 teachers. Oh happy day! And they created huge new untested programs like the one Houston Landing reported on last week.

How? How do you spend more money when your bank account is shrinking? Aha! COVID money.

In March, 2020, the feds started handing out “ESSER” funds – elementary and secondary school emergency relief money. Houston got $350 million a year. The state kicked in another fat subsidy somewhere in the region of $100 million.

For three years. Not forever. Three years.

Nobody said for COVID what. Just COVID because. But the federal money at least came with a specific warning that it not be put into ongoing programs and salaries that would have to be funded by some other source when the ESSER dollars stopped flowing.

Some school districts took the warning seriously. Aleesia Johnson, superintendent of schools in Indianapolis, put her money into things she knew she could stop doing when the cash flow stopped. She even set up performance metrics in advance so her school board would be able to look back and see whether the money had done any good, and she created a protocol in advance to return her budget to normal.

Not so Houston. Houston’s method for deciding how this new bounty should be spent was to send out a query to everybody in the district asking them what they wanted. A district official described this effort to me as, “What would you like for Christmas?”

The result was things like the nine percent salary increase – baked in forever – along with burgeoning staffing levels, ever-fattening departmental budgets, lavish stipends, ballooning overtime costs and unproven and untested programs like the one the Landing wrote about, called “wrap-around specialists.”

And why not? Free money!

The wrap-arounders are salaried staff members at each school whose job is to connect needy children with services available in the school system and also outside the schools in the community. Maybe it helps. Maybe not. There has been no concerted effort to measure outcomes.

Meanwhile, before ESSER there were 40 wrap-aorunders in the entire school system. Post-ESSER, there are 280.

The budget Miles is about to present will propose cutting about 170 of the wrap-arounders. Apparently there will be serious cuts to headquarters staff, where there has been especially serious metastasis under ESSER.

And, yes, one accomplishment of the budget will be to protect the money Miles needs to fund his reforms, which, again, are aimed mainly at poor kids.

But the big goal – the one Houston media should be focused on – is something called the “fund balance.” A fund balance for a public school district is roughly equivalent to a personal net worth. It’s the total value of everything the district owns and has in the bank or in investments minus its obligations.

Fund balance is important for many reasons but especially because it drives credit-worthiness. If a school district has a threadbare fund balance, it will have to pay through the nose to borrow money, and everything from there on will sort of nose-dive.

If that happens – and it does happen in some school districts, because some school districts are crazy – the state is on the hook to step in and bail everybody out. That’s a thing the state does not want to do. Ever. Hates having to do. Therefore, the state has serious rules and monitoring allowing it to step in sooner and shut down spending before catastrophe. The fire alarm that the state relies on to warn of impending financial catastrophe in a district is its fund balance.

Catastrophe was exactly where Houston was headed on the path that was set by that previous school board and superintendent – the ones everybody thought were so nice. Had their course continued, the fund balance, which was at about $780 million pre-COVID, was slated to plummet to $252 million by 2026.

That’s a 911 call. That’s people with badges showing up from Austin saying, “Step away from the checkbook, now.”

Miles has shared some aspects of his proposed budget with Houston media. Everybody has the graphs shown here, although I haven’t seen them in Houston Landing of the Houston Chronicle. I guess they do sort of spoil the whole Dickensian flavor of the coverage.

The bottom line is that his budget will keep the fund balance at $800 million – the pre-COVID level even though the ESSER money is now gone. Given what happened under ESSER, holding the fund balance at that level will be pretty much a fiscal miracle, especially if Miles is able to keep his reform program on target.

Houston hasn’t decided yet if it will go to voters this year for a big multi-billion dollar capital improvement bond election. If Miles doesn’t get the fund balance shaped up, Houston won’t be able to sell school bonds to drunk people, let alone anybody on Wall Street.

Well, wait. They might be able to sell the bonds to journalists. If only the journalists had some money.

It looks like there was some evaluation of the wrap-around services approach because there was an indication that fewer people were using the services that were not located at the schools. Miles indicated support for wrap-around services, initially at least.

Also, think it was a mistake by Miles not to make the financial situation with HISD perfectly clear with the public when he took over. If he did so, he can point to that declaration now as a reminder.

Of the fund balance: You are aware of the "General Accounting Principles" that apply to school districts?

To summarize training materials on the topic:

Under school system GAAP, supplies held in stock room inventory are typically accounted for using the consumption method. In this method, supplies are recorded as an expense when they are used or consumed rather than when they are initially purchased. When supplies are received into the stockroom, they are not immediately expensed. Instead,

<em> they remain as an asset (inventory) until they are taken out and used. </em>

The expense is recognized only when the supplies are issued for their intended purpose (e.g., distributed to classrooms, offices, or other departments).

So, part of any "positive" fund balance may, possibly, include a freezer full of chicken sticks with an expiration date of 2019. Or unopened boxes of Pentium laptop computers running Windows XP. Or a pallet of salmon colored copy paper. It might, in worst case, include the value of stuff that has been issued, thrown away, or pilfered without the inventory accounting being updated.

A district may, in my direct experience, report a fund balance of some six figures greater than any cash on hand available for payroll or fuel or repairs ... Districts with poor administrative controls over kitchens, closets, stockrooms, vehicle parts lockers can be in a world of hurt long before the problem shows up in the annual independent audit, and even then, the auditors are much more accustomed to look at the journals instead of dusty old warehouse shelves.